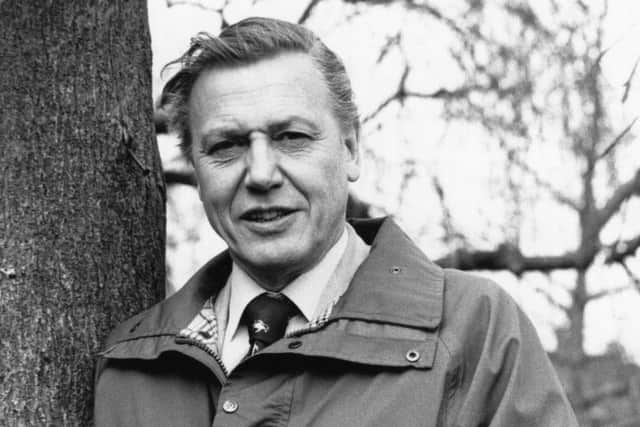

Barry Band: How Sir David Attenborough's teeth nearly put an early stop to his TV presenting career

A few weeks ago, playing Sherlock in the Grand Theatre’s 125-year story, I said no actor had a career that could compare with Richard Attenborough’s.

The role that made him a star – Pinkie in Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock – was premiered at the Grand in February, 1943.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSince then, I’ve been “doing a Sherlock” in charity shops for a book I knew included the early days in TV of Richard’s equally famous younger brother, David. The “bingo moment” came last Sunday in the Hospice shop in Lytham. There it was, lying on a table as if left specially for me. Sir David Attenborough’s 2002 autobiography, Life On Air. Clever title!

Sir David is forever “on air” and is still creating shows at the age of 92. But how did it all begin?

A speed-read of a few pages sold me on the book (£1.50), for Sir David’s story is perfect Memory Lane material – interesting to old-timers who remember the early days of TV and to the young’uns who will be amazed today’s super-slick viewing technology began in primitive conditions.

After studying natural sciences at Cambridge, in 1952 Sir David joined a three month course at the BBC, with no certainty of getting a job. He was steered into doing a live interview, but it didn’t go well and he wasn’t asked again. Decades later, he found out why. The lady who first engaged him had written a memo: “David Attenborough is intelligent and promising and may well be producer material, but he is not to be used again as an interviewer. His teeth are too big.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt might have ended there for the broadcaster admired round the world but, he said in the book, he was given a further six month period of employment, as an assistant producer in the Talks Department. Talks covered everything that could be described as non-fiction – books, current affairs, science, arts, gardening, DIY, knitting, medicine, politics, travel, he wrote.

“No one had made television programmes on these subjects before, so there was no accepted way of doing so.”

Does that sound as if they made it up as they went along?

There will be few people who can remember one of the Talk Department’s creations, Animal, Vegetable, Mineral. A museum would challenge a resident panel of archaeologists, art historians and anthropologists to identify odd objects. How exciting was that? But the show did produce, in the figure of the chairman, the moustachioed Sir Mortimer Wheeler, one of the first big personalities of TV.

Sir David recalled the experts were wined and dined before the ‘live’ show and there were occasions when a participant over-imbibed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn his book, Sir David described the early cameras as tin boxes mounted on pram wheels. The cameras often failed during live broadcasts and staff had to improvise. Sometimes a halt would be called by the engineer and viewers would be treated to a stand-by film of a kitten playing with a ball of wool, waves crashing on a rocky shore or – a particular favourite with viewers – a ball of clay rising and falling beneath someone’s hands on a potter’s wheel. Remember those?

Sir David recalled in the early ‘50s shows were broadcast live. The BBC was strapped for cash and only one or two shows per week were pre-recorded.

And he commented on the BBC being called Auntie by the press.

“If Auntie did exist she tended to regard the fashions and moral attitudes of yesterday being eternal. She was dignified in language and manners and certainly knew what was best for people,” he wrote.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Auntie also had a view on what and when viewers should view. News, it was felt, was not really suitable for television. Pictures were not to be trusted.”

There was no telly in the morning, when people were supposed to be at work. There were two hours in the afternoons for housewives to hear about knitting, cooking and similar domestic subjects. And TV stopped until the evening, when programmes were introduced by a male announcer wearing a dinner jacket or a young lady in an evening gown.

After only 25 pages of the book, it became clear it was a treasure trove of “hard to believe” moments, remembered in an entertaining way. In an attempt to make Talks programmes more relaxed, the lady in charge thought they should take more risks and find some raconteurs, natural gems who could come to the studio and, with little rehearsal, sit and sparkle. Like Bill, the rat catcher!

The programme that set Sir David off on his career documenting the natural world was Zoo Quest. In 1954, he and his small team went to Sierra Leone, to film the wildlife. They used a 16mm camera, driven by clockwork. It could run for only 40 seconds before it had to be rewound and its 100ft rolls of film gave only two minutes, 40 seconds of pictures.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt ran for several series from 1954 to 1963, with a parallel purpose of collecting animals from around the world for London Zoo, before Sir David became controller of BBC2 from 1965 to 1969.

It was another 10 years before he wrote and presented Life On Earth, setting the standard for his amazing natural history features, which continue to this day.