Story of Fylde's lost film studios

When films were still silent, they were being turned out all over the country - in London, of course, but also in less likely places, such as Brighton and Shoreham-by-Sea, Bradford, Sheffield and even Holmfirth.

The biggest stars were often American, but as the Twenties roared by, the industry changed again.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBritish companies began to grow, and so did the pressure to show more home-grown films.

And that’s what brought Sir Lindsay Parkinson into the business.

The Blackpool builder had been the town’s mayor during the Great War, and its MP for a little while afterwards.

But in 1928, he announced that he was going to build the biggest film studio in the country.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSir Lindsay was one of several men behind a company called Lancashire Screen Productions.

There was also a man who owned a printing concern, and one who specialised in doing deals in the USA. While the job of actually making the films was given to George Dewhurst.

He came from Penwortham and had once been an actor.

He had been a director in Berlin when that was all the rage, and he claimed to be able to turn out pictures in record time.

George promised to base himself on the Fylde, and he said he would make his films on Lytham Green.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

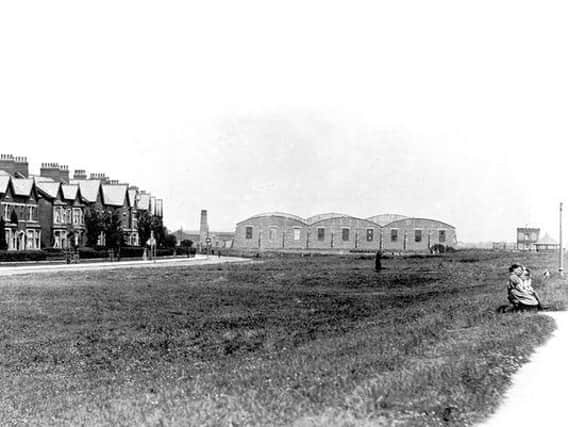

Hide AdThe studio in which he would make the films was to be at the east end of the Green, just beyond the place where the Land Registry building would later stand, on land now occupied by houses and crossed by Victory Boulevard.

George said he had travelled all over the country, and the light there was the best he had seen.

This was already an industrial site.

Since the Great War it had been the place where flying-boats were built for the Admiralty.

There was a slipway that ran down to the Ribble, and close by, two enormous sheds.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

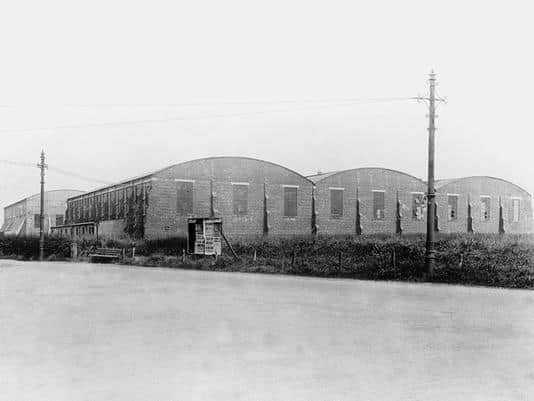

Hide AdSince 1920, one of those sheds had been occupied by the Parkstone Film Company.

Founded by two Manchester men, this company would remain in business for much of the decade, and its workers would become a familiar sight, as they made their way along Preston Road.

The man in charge of the Lytham site, Walter Buckstone, had travelled through India, China and Japan, and been a cameraman on the Western Front.

The Parkstone shed was the more westerly of the two, and its floor area was said to be larger than that of Blackpool Tower.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was so large, indeed, that it could accommodate a dozen film ‘sets’ put up side-by-side – a kitchen or staircase here, a book-lined library over there.

And while the natural light might have been excellent, nothing was left to chance.

Large lamps were placed around the studio, powered – because Lytham still had no electricity – through a cable run from the tramway, which ran right outside.

Next to their shed, the Parkstone company put up offices, dressing-rooms, and rooms where films could be developed and printed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was even a small cinema, fitted out with tip-up seats and a projector, where the finished product could be checked through before it was sent out into the world.

Parkstone’s films were exhibited in picture houses across the county – in Burnley, for example, at the Savoy Cinema, at the Piccadilly in Manchester and the Bolton Hippodrome, and most often at the Picture Pavilion inside Blackpool’s magnificent, doomed Palace complex.

There were golf films and tennis films, Blackpool’s first carnival, and bowling at the Waterloo tournament.

And in Football Personalities, audiences were taken behind the scenes at Old Trafford, Goodison or Ewood Park, and shown the players preparing for a game and relaxing at home.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHare-coursing might be shown, or the Grand National, or a diocesan trip to Lourdes.

And after the Prince of Wales visited Southport, the Parkstone cameraman flew his footage back across the Ribble for developing, and then flew the completed film back to Southport so it could be shown to a paying audience before the day was out.

As Parkstone had, Lancashire Screen Productions took an interest in the Lytham site, and at the end of 1928, it paid £40,000 for its own portion of land there.

Within days, however, it had changed its mind.

Early in the New Year, the company announced that it now planned to build its studio on a different site – one closer to Blackpool and easier to reach. The plans for Lytham would now have to be cast aside.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe new place could be found on the Little Carleton estate, just off the road out to Poulton.

It was covered with meadows and old trees, even if it was also wedged in between Blackpool Old Road and the main railway line.

The company would pay far more for this site than it had for the flying-boat factory, but the benefits would be greater as well.

There would now be not one, but two studios, and each of them would be longer and taller than the one in Lytham.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd that wasn’t the only grand announcement Lancashire Screen Productions made.

George Dewhurst promised that the new studios would find work for local people, many of whom would be enticed back from film jobs in the South.

And they would all be set to work creating proper Lancashire stories.

The first two films would be dramas about the cotton industry and the trawlermen of Fleetwood, and they would be written by Eliot Stannard, who had won praise for his work on Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lodger.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe third film might be about life on the streets of Liverpool.

The company would produce seven feature films in the first year alone, George said, together with a weekly newsreel designed to appeal to local audiences. With luck, the cameras would be rolling at Little Carleton by Easter.

But that wasn’t to be.

Film quotas weren’t the only change facing British cinema.

The Talkies had to be confronted as well, and ultimately, they would see off George Dewhurst and Sir Lindsay Parkinson.

Few people at Little Carleton had thought about the question of sound recording, and after The Jazz Singer and everything that came in its wake, Lancashire Screen Productions suddenly seemed very old-fashioned indeed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe company was wound up in November 1930, without any of its planned films – or its huge new studios – having been completed.

George Dewhurst himself went bankrupt a few months later, owing more than £300,000 in today’s money.

And though Little Carleton would be home to many businesses over the years, a massive film studio wasn’t among them.

Back in Lytham, an 11-year-old boy would be brought up before the magistrates on a charge of theft.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe had forced his way into the Parkstone shed, which now stood abandoned and crumbling, and taken away some projector parts and a few boxes of old, silent films.

The boy said he was sorry for what he had done, and he was bound over for six months.