Life as newspaper reporter in 1970s Lancashire

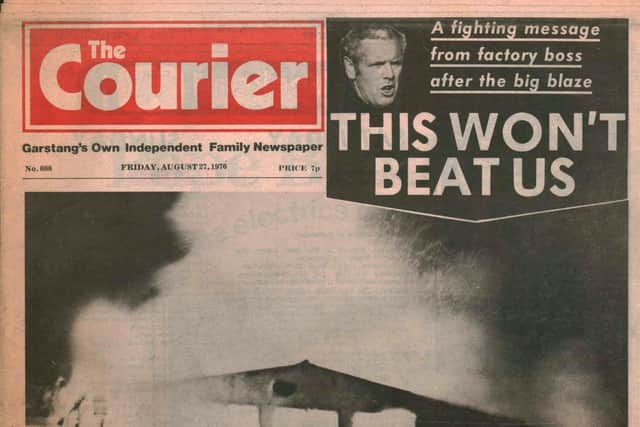

I was getting ready for bed one night when the phone rang. It was PC Ted Norris, Pilling’s policeman. “Get yourself to Garstang quickly as soon as you can,” he urged. “There’s been a big fire at the CCM factory.”

I got dressed, clambered into my Mini and sped off into the night, unaware I would be about to cover one of the biggest stories of my career. The CCM clothing and workwear factory in Windsor Road was the town’s biggest employer, with a staff of around 200.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen I arrived the factory was a mass of flame. Crowds watched in stunned silence as firefighters battled in vain to conquer the blaze. Many were in tears.

Trying to interview people that balmy August evening in 1976 proved nigh-on impossible. Most were too shocked or upset to speak.

The next day, as workers congregated at the charred factory remains, the company’s managing director Michael Watson pledged the firm would be back in business. He vowed no-one would lose their jobs.

True to his word, production resumed at a temporary base in Oakenclough three months later. Less than 12 months after the blaze a new factory was up-and-running on the Garstang site. If ever there was an example of a phoenix rising from the ashes, this was it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

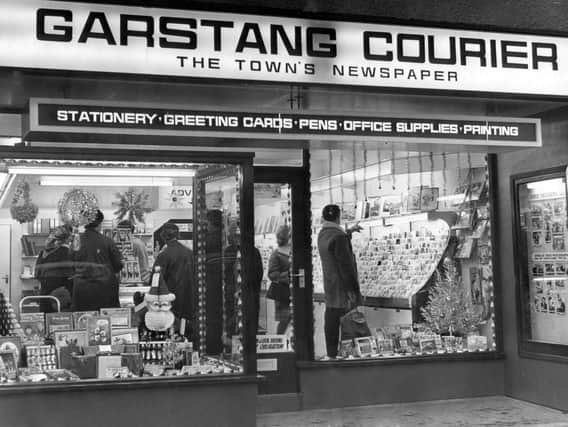

Hide AdNot all my stories were as dramatic as this. Back in the 1970s Garstang was a small market town with a population a fraction of the size it is today. In our sleepy rural backwater very little happened in the way of ‘hard news’.

Crime was generally very low, there were no major industries and we were a world away from celebrity gossip or political scandal – unless you counted the shenanigans at the local council meetings. Covering town and parish council meetings, the magistrates’ court, agricultural shows, galas and field days, WI news and shopkeepers’ battles against double yellow lines… these were the kind of things we relied on to fill the paper each week.

‘Human interest stories’ – vicars retiring, headteachers leaving, golden weddings, births, marriages and deaths – were also the bread and butter of a small weekly paper, boasting a circulation of 5,000.

But news didn’t come to us gift-wrapped – we had to get out there and find it. As a roving reporter I was tasked with building up a network of contacts among local police officers, headteachers, clergy, councillors, WI members and anyone else who could be relied on to provide me with ‘news’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn a never-ending quest for stories I’d scour notice boards and shop windows. You never knew what you might find lurking among the adverts and posters in shop window. One of my most memorable stories came from a postcard in a post office window. It was an appeal from a woman for someone to become an adopted ‘grandma’ to her three children. After jotting down the telephone I arranged to see the woman who told me her heart-warming story.

Two or three times a week I’d call at Garstang police station, where the sergeants and duty officers on the inquiry desk would flick through bulging files containing reports of crime and road traffic accidents (there were no computers to record incidents). With crime generally very low, most of the news I picked up centred on domestic burglaries and agricultural theft, including poaching.

Back then each village had its own police house staffed by a local constable. Through my work I got to know all the village bobbies, none more so than Pilling policeman PC Ted Norris, who went on to become my father-in-law after I became acquainted with his son Keith when knocking on the door of the village police house looking for news.

There was one way I could guarantee filling up my notebook - and that was covering the monthly meetings of Garstang Town Council and Preesall Town Council. Back then councillors were trying to adjust to the changes ushered in by the 1972 Local Government Act, which, in 1974, led to the creation of a new district council, Wyre Borough Council.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPerhaps not surprisingly, these radical changes led to local councillors frequently becoming hot under their municipal collars. Before reorganisation Garstang Rural District Council and Preesall Urban District Council had operated as self-contained district councils with wide-ranging powers. After the act Garstang and Preesall became ‘Town Councils,’ but with diminished responsibilities.

At meetings disgruntled councillors would vent their fury over their loss of power. Their outbursts led to some memorable headlines, including a demand by a Preesall councillor for the council to ‘Declare UDI’ (The Unilateral Declaration of Independence), emulating the Rhodesian government which, in 1965, attempted to become an independent state. It was a comment driven by anger, but it made a good front-page story.

Eventually things settled down and relationships between the local councils and Wyre Borough Council became more cordial. Away from the furore around reorganisation, traffic safety, playing fields, litter, dog dirt, vandalism were among the matters regularly debated by both councils.

Today’s council business is probably not much different than it was nearly half a century ago, but these days you’re unlikely to find reporters from the local newspapers covering meetings.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMany papers no longer have a base within the community, so reporters are less likely to be present at meetings and events in the way they were in the 1970s.

Garstang Magistrates’ Court used to sit on Thursday mornings, the same day as the weekly market. Minor motoring offences, drunk and disorderly behaviour and shoplifting offences accounted for the bulk of cases brought before the magistrates, but occasionally something meatier would bring reporters from the nationals flocking to the tiny courtroom. The magistrates’ court in Park Hill Road closed during the early 1990s.

It operated as a magistrates’ training centre before eventually being sold and converted into a dental referral practice and flats. Over the past decade four out of 12 magistrates’ courts in Lancashire have closed, the most recent one at Chorley in 2019. It’s a pattern mirrored across the country, with 162 out of 323 courts having shut their doors as part of a government move to increase online access to justice.

During the tumultuous 1970s reports of industrial unrest, fuel shortages, unemployment and the bread crisis dominated the national headlines. The Courier reported on issues that touched on local readers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the lead-up to the European Referendum in 1975, the readers’ letters pages featured a lively exchange of views debating the pros and cons of remaining within the Common Market – a debate which would have uncanny parallels with the furore over Brexit nearly half a century later.

Meanwhile, placard-waving traders from Chamber of Trade and Commerce went on the march to protest against newly introduced VAT and other measures they claimed would force them into becoming unpaid government tax collectors.

One of my most memorable stories came when I covered the Lancashire coastal flooding in November 1977. Not only was I involved in reporting on the floods, but my family home in School Lane, Pilling, was among those flooded that fateful evening. I found myself torn between covering the story and helping my family with the clean-up.

Across the Fylde coast more than 5,000 properties and 7,900 acres of agricultural land were flooded after 36ft-high tides driven by 90mph winds breached sea defences. One farmer lost more than 6,000 chickens and more than 100 turkeys after his farm became engulfed in three feet of water. Several bullocks narrowly escaped death when water flooded one cabin and his entire farmhouse was flooded.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe floods caused an estimated £6,000 damage at Cockerham Sands Caravan Park after the clubhouse, office buildings and shops were engulfed. The park’s managing director described how the force of the tide had completely washed away an access road and breached a nearby wall before water rushed into the clubhouse. It was a similar picture at Knott End Golf Club where the social room was flooded and tiles were ripped off the floor in the gents’ changing room.

Compared to many our family got off relatively lightly from the floods. Damage was confined to the downstairs living room and hallway. Others were less fortunate. Pilling Rose-grower Bert Pendlebury was among those facing devastating losses. Twelve months after the floods he was forced to close his business after failing to get government aid to cover the loss of 30,000 damaged rose trees and damaged glasshouse heaters, worth £10,000.

Looking back, the 1970s were a great time to work in newspapers. We had fun. We worked hard, but played hard. Even though I left journalism when in my mid-30s to pursue a career in health promotion I can honestly say they were the best days of my working life.

That’s News to Me! Tales of a Rural Reporter in the 1970s is available from local shops (see That’s News to Me! Facebook page for details of stockists), priced £12.99. Proceeds to go to St John’s Hospice, Lancaster, and Trinity Hospice, Blackpool.