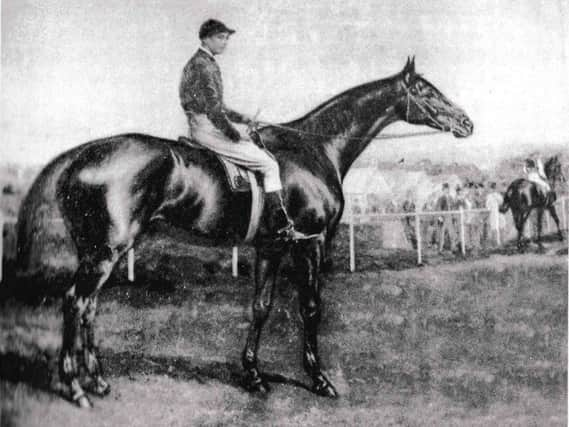

Champion racehorse who came from a Lancashire village

Royal Ascot, Thursday, June 20, 1889. Gold Cup day. For the four days of the meeting, fashionable London decamps en masse to the racecourse, mostly on the 150 trains from the two London stations serving the meeting. As soon as one train departs, another is prepared.

The meeting acts as a magnet for other classes too: the upper crust to see and be seen, middle classes to see and discuss royalty and their fashions and indulge in a flutter, and a range of characters hoping to profit from the crowds; chancers and card sellers, costers and pickpockets and sweet vendors, “the hundred and one types of character that go to make up that strange anomaly, the crowd,” as one commentator put it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Prince and Princess of Wales led the Royal Procession on a warm day. The Queen herself disapproved of the Prince’s horse racing associations and had not attended since the death of Albert, nor would she allow her son to stay at nearby Windsor Castle during Ascot, so he rented Sunninghill Park, two miles from the course.

Their guests included the Comte and Comtesse de Paris, the Marchioness of Londonderry, the Dowager Duchess of Montrose: President Lincoln’s son was there as American ambassador, but only Mrs Lincoln and their daughter’s “white crepe de Chine” were considered worthy of mention in ‘The Queen’ periodical. White gowns were the agreed style for the day, “light yellow and link vests and jabots were a special fashion,” and delicate foulards and parasols “numerous.”

For the first time a booklet rather than a card was produced to list the runners, and at 3pm 13 horses lined up for the Gold Cup, the biggest race in Britain outside of the five Classics. Mr De Rothchild’s Cotillon was a less than hot favourite at 5/4, next in the market were two horses at 5/2, Lord Falmouth’s Rada, and Mr De La Rue’s Trayles.

From the off, though, it was Trayles who made the running. Behind him the two other leaders in the betting alternated places with the eventual fourth, Duo, ridden by 16-year-old Mornington ‘Morny’ Cannon, whose sister Margaret married Ernie Piggott, grandfather of Champion Jockey Lester, but it was Trayles and his jockey, W ‘Jack’ Robinson, who won “in a canter, by four lengths” from Rada and Cotillon.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo, what of this horse and its unusual name which sounds very like the name of the small village between Kirkham and Preston, Treales?

Trayles was bred by Preston butcher and farmer, Thomas Dent Clayton, at his farm in Moorside at Treales. He had a shop on Friargate in Preston, and another establishment at Barnfield, Swillbrook, Woodplumpton, so was obviously a successful businessman.

He had run his favourite mare, Miss Mabel, less successfully in a handful of races, and his near Treales neighbour, Mr James Butler, housed three thoroughbred stallions for the breeding season at his stud farm, including Restless, a dark chestnut standing at 16 hands and winner of the Lancashire Cup, Nottingham Handicap and a handful of other middle grade races.

Restless travelled the district as what was known as a ‘County Sire’, a stallion bought as an investment to improve the region’s bloodstock. The stud fee was 10 guineas, ‘groom’s fee included.’ Restless and Miss Mabel were paired, Trayles was the result. With a further nod to Lancashire village life ‘Roseacre’ was a half-brother.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTrayles was trained by James Hopwood at Hednesford in the Midlands. Mr Hopwood was popular with Lancashire owners because he was from Newton-le-Willows and his first stables were near Bury.

Mr Clayton ran Trayles as a two-year-old on Manchester racecourse, winning one out of three, and twice as a three year old, winning both races. Trayles attracted the interest of larger owners, and after the second victory in 1888 he was sold to Captain Machell, a Yorkshireman but an alumnus of Lancashire’s famed Rossall School, for 2000 guineas.

Captain Machell was a very hands-on owner, and a fine spotter of horse talent, and when he realised he had a potential champion he tended to sell it on, as he had with the legendary Seabreeze.

In the same year, then, he sold Trayles to Mr Warren de la Rue. Now trained by James Jewitt, of Newmarket, he came third in the 1888 Cesarewitch. It was as a four-year-old that Trayles’s career took off. He was essentially a stayer rather than a sprinter and ground down the opposition with his tireless, effortless gait, so was more suited to the longer races.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe day after the Gold Cup he won the Alexandra Plate, a three miler, and later in the season the Goodwood Cup and the Challenge Whip at Newmarket. Mr de la Rue’s colours of ‘orange, red collar, cuffs and cap’ were regularly in the winner’s enclosure.

So who was Mr de la Rue? At the time of these triumphs he was of Regent’s Park, London, and the grandson of Thomas de la Rue, founder of the de la Rue printing company, which produced Britain’s stamps, and those of her colonies’ too.

Warren de la Rue successfully led the company for 22 years, before handing it on, divorcing his wife, and enjoying a more hedonistic lifestyle, “a splendid bachelor existence,” says one biographer.

He was an eccentric, an eccentricity exacerbated by a fall from his horse in Hyde Park. He had a love of gadgets: eccentricity and gadgetry combined in his York Gate house where he had a special lift installed so he could send his false teeth down to his valet for cleaning.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1913 he felt it was time to seek a quieter life and moved to Tenby, where he bought numbers five and six, The Esplanade, cancelled his original plans to convert them into ‘a fine Georgian residence for his own use’, demolished them, and built a modern Edwardian residence with central heating and electricity provided by a steam generator. His bathroom even had a wave machine.

His moments of national fame were not forgotten, however. His house was known as ‘Trayles’, and the sculpture of that horse’s head that he commissioned remains over the entrance to what is now The Atlantic Hotel, is an eccentric yet fitting memorial to both owner and horse.

Thanks to the many interesting and interested people who have helped in compiling this article: the staff of the Atlantic Hotel, the Kirkham and Wesham memories Facebook page, John Griffiths and Tony Hunt of Hednesford, Alan Brindley of Tenby, Roberta Snape, Tricia Gaskell, Samantha Shurmer, and probably others I’ve missed.

“Woodplumpton. Glimpses of a Lancashire Village” is available from the author John Grimbaldeston. You can contact contact John via email, [email protected]