Blackpool's wartime spirit was anything but subdued

J.B.Priestley told the world week by week of Britain’s wartime struggle to survive. From April 1940 he attempted to rally the world, and particularly the United States, to Britain’s cause.

Published for the first time, these overseas broadcasts, Britain Speaks provide a fascinating record of the People’s War.

Blackpool 1940

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“They were quite right when they said I must not leave Lancashire without paying a visit to Blackpool.

Now, some of you who are listening probably know Blackpool better than I do, but for the benefit of some of the others, I’d better explain that Blackpool, which is situated on a flat, bleak part of the Lancashire coast, is the most popular seaside resort in this country.

It has been known to deal with half a million visitors in a day. It’s the English equivalent of Coney Island.

There is absolutely no natural beauty whatever in Blackpool and its immediate neighbourhood, so the town has always concentrated on providing its visitors with the maximum amount of amusement, which includes, at the height of the season, a gigantic fun fair, three piers, a famous circus, many different vaudeville shows, dancing on a vast scale under the well-known tower and at the Winter Gardens, music of all kinds, and all manner of genial nonsense. Blackpool is the favourite holiday town of the North Country working people, though it’s by no means confined to them.

I’ve known it all my life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe last time I was here was during the Munich crisis, when I came here because I was trying out a new comedy. It was Illuminations Week in Blackpool, I remember, and we did enormous business at the theatre, but

I also remember that I hated it all – I hated the Illuminations, I hated the town, and above all I hated the Munich settlement.

But what a difference then and now! That week the promenade for miles was nothing but an endless glitter of lights, the very street cars flashing and glowing with coloured lighting.

Now, the whole length of that promenade – and I believe there’s about eight miles of it – is in darkness. On the other hand, the spirit of the place is anything but subdued. War or no war, Blackpool is Blackpool still, I’m delighted to say.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt may have lost most of its usual holiday-makers, but in their place it has new – and more interesting – types of guests, for the boarding house accommodation of this giant among seaside towns has been put to good use.

It is now, in fact, the very oddest mixture. For example, it has many civil servants still here, though nothing like as many as it had. I have a feeling that the civil service, which is not inclined to be hearty and democratic, and Blackpool, which is very hearty and democratic, don’t make a perfect match.

The Blackpool landladies, who are lavish with their food but not with their bedroom and sitting-room space, couldn’t understand why these haughty people from London wanted so much room to themselves, and suspected this exclusiveness.

Much more popular guests are the many lads in the Royal Air Force who swarm into the town whenever they can get enough leave – and a fine time they have of it too. To begin with, the Blackpool caterers and landladies take a pride – at once professional and Lancashire – in keeping a generous table. Then they’re in what is probably the healthiest town in England, swinging along a promenade swept by bracing sea breezes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThen everything possible is done to make them welcome. Then the town provides them with innumerable clubs and canteens, and in addition allows all these men of the services admission into all the theatres, vaudeville shows, dance halls etc. at half price.

For a few pennies, a man can have a long gorgeous evening’s amusement. Good lord! – if I’d been stationed here as an Army recruit, twenty-six years ago, I’d have thought I’d been sent to paradise.

But not all the airmen here in Blackpool are British, for Blackpool attracts large numbers of visitors also from among men of the Allied Air Forces who are now in this country.

They also are welcome, all of them, but the special favourites seem to be the Poles, who in their turn obviously regard Blackpool as their special favourite. Many of these men reached this country after incredible adventures in Poland and then in France. I couldn’t help thinking, while I was talking to some Polish officers yesterday, how widely incongruous and unexpected all this was – that Blackpool of all places should now have as visitors men from Warsaw and Krakow, from the shores of the Baltic and the banks of the Vistula!

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey are a fine lot of men, those Poles, as gallant and dashing in the air as they are when they are amusing themselves on the ground. And that is saying a good deal, because there can be no doubt that, to the delight of the visiting comedians, who now find a whole series of jokes ready-made for them, these Polish airmen, members of an ardent and amorous nation, have played havoc among the more susceptible young women of Blackpool, who have undertaken the rather dangerous task of teaching them English with great enthusiasm.

Last night, I looked in at one crowded vaudeville show, where one of London’s favourite comedians, Bud Flanagan, was appearing. Bud announced to his partner that he proposed to pop off and pick up a nice girl. His partner said that no girl in her senses would want to have anything to do with him. ‘Ah, but you see,’ said Bud, a grin lighting up his mournfully droll face, as he showed us what he’d been hiding behind his back, ‘I’m all right. I’ve got a Polish cap.’ And there was a tremendous roar from the packed house. That shows the sort of welcome the gallant Poles have from this large-hearted Blackpool.

Then, in addition to these visitors of the fighting services, there are thousands of evacuated women and children here.

This does not leave much room for ordinary visitors, who come in search of bracing winds and quiet nights, but there are as many as can be accommodated, and it is now hard work finding a bed in Blackpool.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI gather too that a great many vaudeville people now make Blackpool their headquarters. As well they might, for it seems at the present moment to be Britain’s number one entertainment town. Last night, the manager of the town’s amusements took me with him on a quick conducted tour of them, and I found one star after another playing to the crowded houses.

At one theatre we visited, the Grand, one of New York’s favourite comediennes, Beatrice Lilley, was delighting a huge audience with her sly and perfectly timed drolleries. I had a word with Miss Lilley afterwards, and asked her why she – who, by the way, was paying her first visit to Blackpool – had stayed on in England when she must have had many tempting offers from New York and Hollywood.

And I liked her reply: ‘Well, one just couldn’t leave, could one? I wouldn’t like to be anywhere else now, though I love America.’ And that, you’ll agree is the spirit.

Then we went on to a huge vaudeville theatre, the Palace, to see the final item – the comedians – in a variety show, and I must confess that although the comedians were very good, it was the great audience, balcony upon balcony, that I watched from my box.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey were all roaring with laughter, but I wasn’t. To tell you the truth, I felt strangely and deeply moved, partly because the sight of such an audience has been so rare lately, and reminded me of happier times – after all, I’m a bit of a showman myself, you know – but also because there is a kind of innocence about a great crowd enjoying itself, a suggestion of a universal childlike quality in us all, and suddenly to discover this again, embedded in the horrors and miseries of this war, seemed to me very moving.

One of the comedians gave a wonderful impersonation of an oldish Lancashire women gossiping to her neighbour over the garden wall, and during this gossip he kept pretending to be annoyed with some children, and in one of his sudden shouts to them cried, ‘Now put that shrapnel down,’ which brought a roar from the audience.

And I thought how strangely our lives had been shaped that we could find it funny that our children should be playing with shrapnel. Death comes roaring from the skies at night, and then in the morning the children are playing with what remains of the recent menace.

Curiously enough, this same comedian, whom I ran into later, had with him a bit of shrapnel – though ‘casing’ would be a more accurate term for it – that had penetrated the roof of his car and hit him on the shoulder only a few nights ago, outside another city.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAll these entertainers are working desperately hard, not merely in their particular shows, but also travelling at all manner of hours to charity concerts or entertainments for the fighting men. The two-star comics of the evening, Flanagan and Allen, told me that in a week or two they are taking a fortnight off from their tour to return to London specially to amuse the folk in the air-raid shelters.

And that, you’ll admit, is the right spirit too.

I found when I received my bill at the hotel this morning that Blackpool’s boast that it did not allow war profiteering was no idle one, for although the demand for rooms at this particular hotel is so great that I’m sure I would never have found a bed in it if I hadn’t been doing a semi-official job in connection with the town and strings hadn’t been pulled, yet there had been no attempt to make capital out of this situation. My bill was no more than it would have been at any time, very reasonable indeed.

I wish I could say as much about all parts of the country – but certainly in Blackpool they are trying not to take advantage of the war, and to give the visitor a square deal. But then Blackpool is a hearty democratic resort – none of your snobbish nonsense about being ‘exclusive’ there – that has always catered chiefly for the working folk, who were dancing in the great ballrooms of the Tower and Winter Gardens long before dance palaces sprang up everywhere, and so it is taking care to behave in a sensible, hearty, hospitable, democratic fashion.

My only complaint – and this is not the town’s fault, but rather its misfortune – is that so much of the town’s accommodation has been taken over that not enough is left for the general public, many of whom could do with a week of its bracing air, long wide promenades and huge amusement palaces. In fact, I could do with a week or two of them myself, but no such luck. Still, it was good to catch a glimpse of such an old friend. Which reminds me that on Sunday I want to talk to my friend Harvey Mott, newspaperman of Phoenix, Arizona. And will somebody tell him, please? Goodnight.” Buy the book hereAustin Mitchell writes...

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

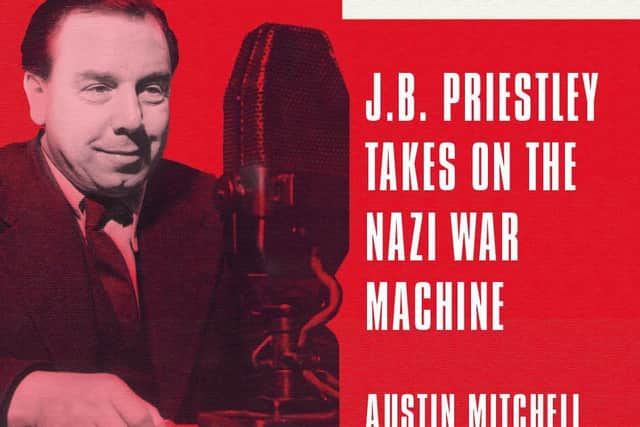

Hide AdIn 1940 JB Priestley, the great author and playwright became the greatest broadcaster of his time as well, with the biggest audiences of everyone else on air except Winston Churchill himself.

He reached them with two series of programmes.

His Postscripts after the nine o’clock news on Sunday successfully built up Britain’s morale in its darkest hour as Blitzkrieg bombing began and the threat of invasion loomed from a Nazi army which had successfully defeated all the powers, France, Holland, Belgium and Denmark on the European coast.

His second series, Britain Speaks went out on short wave twice a week to the United States and the Commonwealth to report how Britain was facing

its worst ever threat and win their support.

Britain Speaks was much less well known than the Postscripts - in fact many of his Tory critics who objected to him being given air space to preach socialism didn’t know it was going out.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI was much more successful in showing how Britain was mobilising and fighting back in the face of the enormous threats, so I was really excited when researching in the BBC archives to find the scripts for these broadcasts, most of them previously unpublished, running through to 1943.

They provide an exiting picture of Britain in the worst part of the war and one which was better than all the other descriptions from the American reporters like Ed Murrow and the British journalists who were all concentrated in London.

Unlike them, Priestley went out of London to look at the effects of the People’s War on the real people of beleaguered Britain.

Naturally the first place he came to was the North from which he sprang.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYou can’t come to the North and miss its play ground - Blackpool.

He arrived 80 years ago in October 1940 to find no Illuminations because of the blackout, no tourists because of travel restrictions but a flood of trainee airmen, particularly Poles as well as most of the big figures of the British entertainment industry.

Blackpool had become Britain’s entertainment focus and the mainstay of ENSA, the unit formed to entertain the troops wherever they were.

Blackpool was playing its part in building morale not of the governing classes of which Priestley was so critical but the morale and good clear of the party, something which has always been its role.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad*Austin was Labour MP for Grimsby from 1977 until 2015 and is a former member of the public accounts committee. Born in Bradford, Mitchell was educated locally before attending Nuffield College, Oxford. From 1959 to 1963 he lectured in history at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand and was a journalist at Yorkshire Television from 1969 to 1977. Britain Speaks has been published by Great Northern Books, who publish a range of fiction and non-fiction titles by J.B. Priestley. The book is available from Great Northern Books, call 01274 735056 or visit www.gnbooks.co.uk

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.