Dying to be thin: The dark reality of life with anorexia

and live on Freeview channel 276

While others might bemoan gym closures as they struggle to shed those extra rolls caused by the extra-cheesy takeaway pizzas eaten during lockdown, I hereby swear to forsake diet food, throw out the protein bars, and firmly ignore various trendy cauliflower-based recipes which 'taste just like real pasta/pizza/rice, honest!'

Really, how hard can it be?

For a recovering anorexic like me, it can seem impossible.

It started, bizarrely, with a newfound love of home-made soups. Tomato, mushroom, spicy carrot and parsnip. I was 9st 11lbs, and at 5ft 8ins I was perfectly healthy with no reason to pursue weight loss at the beginning of 2018. But months of water-based dinners caused the pounds to drop off anyway, and before I knew it I became an addict. Depression, disappointment, despair could all be endured with the help of the reliable, ever-shrinking number on the bathroom scale.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGradually, I began dropping certain foods from my diet - cheese, potatoes, red meat - and eventually whole food groups. Spurred on by cultish keto-dieters and toxic online 'pro-ana' forums, I became convinced that carbohydrates were the devil. Dairy products, too, could not be trusted, and the only meat that was safe for me to eat was plain white fish. I became an obsessive calorie counter and a caffeine addict, drinking mug after mug of black coffee topped up with sugar-free sweetener to kill my appetite. If I did eat, it was fast and frenzied and followed by fifteen minutes of self-induced vomiting.

A pervasive myth about anorexics is that we lack the ability to feel hunger. But refusing food is not synonymous with not wanting it. My desire to eat was persistently, painfully and sometimes overwhelmingly present throughout my whole starvation process. The more I starved the hungrier I felt, and so I started to believe that I could not be trusted to eat. If I did, I wouldn't be able to stop. You're greedy, the anorexia told me. I plummeted to just 6st 10lbs - a BMI of just over 14 - putting me at severe risk of heart failure. My hair fell out. My bowel movements ceased for weeks on end. Still I felt like a fat person in an emaciated body, convinced that any meal that would satisfy a regular person would only tickle my hunger, and would lead to bingeing and, inevitably, ballooning.

So I continued, shrinking my body and starving my brain until I was nothing but a frail, translucent shell in which to house the disease that had sunk its claws into me. I fell into bed at 9pm every night, exhausted, and dreamed of crusty bread with cheese, pasta with vine-ripe tomato sauce, cheesecake and chocolate... and woke up worrying that simply the thought of such indulgences would make me fat. I had to be lifted out of bed. Every morning before work I would sit in my car - freezing despite my three coats - gathering my strength simply so I could bear the weight of my clothes, open doors and climb stairs. There was no room left inside me for anything but the disease.

After spending a few days with my family (during which time I spent hours glued to the radiator, drinking mug after mug of green tea) I was confronted by my sobbing sisters who were sure I was dying - which, of course, I was. Subsequent half-hearted attempts to put on weight led to feelings of self-hatred and anxiety, and were eventually abandoned. I had grown too weak to fight.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMeanwhile, the shadow of Covid-19 loomed over the country. As a key worker I was expected to keep my nose to the grindstone, but my work had been suffering for months due to my ailing health. As lockdown descended so did the grim reality that if I failed to change, I would be dead within a few months. When I collapsed in my home from the effort of getting off the settee, I feared it was too late - I had punished my body too severely, it could no longer remain alive.

My first appointment with a specialist, after nearly three months of waiting, was cancelled due to lockdown. But we continued our appointments over the phone. Meanwhile, I threw myself into the world of recovering anorexics, watching vlogs, reading articles and taking their advice. I deleted my calorie counting app and put my scales away.

As if it was an animal, sensing it was cornered, my anorexia's survival instinct kicked in and pulled dirty tricks in an attempt to sabotage me. I was allowed breakfast only if I did an hour's run first. The yoghurts my therapist suggested had to be the tiny made-for-toddlers kind, sandwiches were made with paper-thin crackers instead of bread and with only the faintest smear of low-fat cream cheese. But there is no compromising with an eating disorder. I had a breakdown after eating two bowls of Morrison's own Fruit'n' Fibre for supper.

One summer night, after a particularly miserable evening spent eating fruit loaf, I woke up at 2am, ravenous and furious. I dragged several Easter eggs that I had bought on discount out of my wardrobe and consumed them in a shameful feral state on the floor of my bedroom.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI went back to bed, woke up at noon and made myself two enormous tuna melts - something I had craved for more than a year - and ate them along with a whole box of white chocolate truffles I had been gifted the Christmas before.

For weeks I flew in the face of my eating disorder, practically inhaling all the foods I had denied myself for so long, from full packets of cookies to simple things like beans on toast and jacket potatoes. This is a daunting process known as 'extreme hunger' in the world of eating disorders. After months of living on black coffee and rocket leaves, I was desperate for high-calorie, easy energy. I also experienced hypermetabolism, which is when your body kicks into overdrive as it furiously repairs all the damage to your organs, resulting in gushing night sweats. I took 16 pills a day to prevent re-feeding syndrome, a potentially fatal condition which can occur after long periods of starvation.

Slowly, slowly, my brain began to wake up. I started writing again, drawing again, playing the piano again. As the effects of the famine wore off and my body got used to a healthy supply of food, the urge to eat constantly also faded. My fears that I would never be full were unfounded - the product of a seriously sick mind. I stopped craving junk food and ate fruit instead. It no longer mattered if I couldn't fit into 24-inch waist jeans. I learned to appreciate jogging bottoms instead.

Re-feeding took months and was accompanied by a myriad of challenges, but eventually I was well enough to return to work - and if anyone thought I was fatter, well, they didn't mention it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo, nearly one year on, would I say I have recovered? Partially.

After stuffing my face to a healthy 9st I hit a mental block and am now stuck firmly in the dreaded 'quasi-recovery' stage many anorexics suffer through. My diet has broadened, but I no longer eat freely and often force myself to go hungry during the day because I feel like I should be satisfied with the healthy meal plan I have set for myself. This, combined with two to three hours of gentle exercise each day, has unfortunately caused me to drop once again into the 'underweight' category - though not as severely as before.

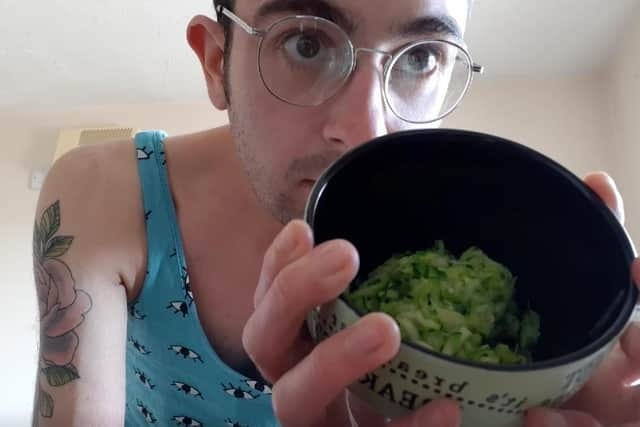

I am aware that I have fallen into the trap of attempting to reason with my disorder. The fear that I was gaining 'too much' after clawing my way to a just barely healthy BMI is proof enough that it still has a hold on me. Some people spend years in this 'recovered... sort of' state but I'm determined not to be one of them. Beating anorexia means facing all the fears that come with it, including the possibility that I may put on more pounds than I am comfortable with. So this year I resolve to enjoy a good curry or a chippy tea every once in a while, and eat a plate of pasta, which I last enjoyed sometime mid-2019. I give myself permission to have seconds if I'm still hungry, even if I think I shouldn't. So what if I gain weight? So what?

The demand for eating disorder help and support has soared in the past year.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRebecca Willgress, of Beat, the UK's leading eating disorder support charity, said: "The coronavirus pandemic has had a significant impact on people with eating disorders. Demand for Beat's services have increased 202% from November 2019 to November 2020. People have struggled with the disruption to normal routine and the loss of their support network both through treatment that has been paused, stopped or changed due to social distancing restrictions and also the lack of support from friends and family as we have been directed to isolate ourselves from others. Our Helpline Advisors have heard from people who found getting access to their safe foods for meal planning really difficult and others who have struggled with the increased amount of food which is in the house either through people stockpiling or shopping less frequently than previously.

"Unfortunately there are many hurdles to recovery for people with eating disorders. Beat would like to see anyone affected by an eating disorder - no matter their diagnosis, gender or background - to be able to find effective treatment quickly and close to their home. For this to happen we need to see additional investment by the UK Government, and increased knowledge of eating disorders for health care professionals as well as the ability for people to recognise the symptoms of eating disorders in themselves or someone they care for. Often treatment offered is a postcode lottery and we hear too many stories of people experiencing difficult conversations with healthcare professionals because of the lack of education they have on eating disorders during their training.

"Eating disorders are often associated with middle-class, young, white females and this stereotype can make seeking treatment or even realising eating disorder behaviours exist very difficult for those individuals outside of this bracket. People who fall outside of the stereotype tell us they found it really difficult to come forward because of the shame and stigma they felt."

If you or anyone you know is struggling with an eating disorder, call the Beat helpline on 0808 801 0677 between 9am and 8pm on weekdays, and 4pm and 8pm on weekends and bank holidays.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.