From Lancashire farmer's fields to war's frontline

I thought – well, this looks rough – but it was nothing to what I saw later on’.

For a quiet country lad in 1916, even a journey to Fleetwood was an exciting experience, as it was for young Alfred Higginson when he went with his brother Joseph to enlist “under the Derby scheme.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBecause he helped with the family farm, Fred wasn’t called up until May “to help with the seeding, ” but then on the 17th, with other young men from Pilling, he went from Pilling station to Garstang Town Hall to report for duty. He was 24, and a keen diarist, so he has left us a wonderful record of his experiences

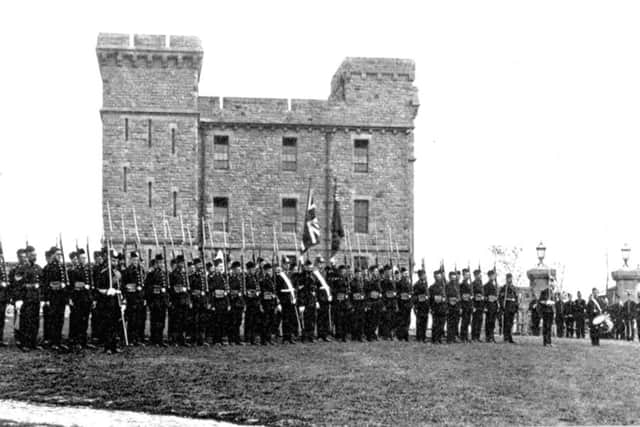

At the Town Hall the men were handed their attestation papers, and then marched through to the station again for the train to Lancaster and their gloomy destination, Bowerham Barracks. Alfred was glad to have the company of fellow Over-Wyrers, Tom Cookson (“Mill Tom”), James Brown, Fred McNeal and “young Swindlehurst, Joe Gornall’s son-in-law.”

A quick medical followed, which involved standing naked in front of two doctors and then jumping over a form, and each was assigned his regiment. For Fred it was the Royal Field Artillery, and that very night he was sent to Fulwood Barracks.

It was three days later that he was finally given his kit, and there were so many new recruits he had to sleep under canvas on Fulwood Hall Lane, then they marched to the barracks for breakfast. After basic training and a final seven days’ leave, Fred was sent to the public baths in Preston for a good scrub, and then on to Woolwich, London, to the Royal Artillery depot.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHere he received extra kit, his identity discs and pay book, and then to Paddington, “after a lot of shouting and hand-shaking by women and children and others,” to Southampton, and finally to Harfleur in northern France.

Here he was tested on his ability to aim and fire the guns, and thankfully he passed; those who failed were put in the Trench Mortar batteries, known as “suicide clubs”. His first few days were spent unloading ammunition at Le Havre, but within the week he was sent to the Front.

“The officer commanding came out and inspected us with our tin helmets on - we looked funny. He made a little speech, told us we were going to the firing line, told us to do our duty and kill as many Germans as we could and not to trust them.

“If any got prisoners in our hands we had not to show much mercy with them. He also alluded to them sinking our food ships and hospital ships and also firing on lifeboats. He got excited at the finish and said Good night, boys, and Good Luck to you all’.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey were all packed tightly into airless cattle trucks and moved via Rouen to Albert. “Morning came, fair weather but lots of mud, drivers with gun limbers and wagons with six horses to each wagon were coming into Albert for shells. They were clear covered with slutch and mud. I thought – well, this looks rough – but it was nothing to what I saw later on. After breakfast, bully beef and hard biscuits, we were marched off to Becourt where the Amm. Column were.”

His first job was to take the shells from the depots behind the lines through to the big guns. He and a friend made a rough shed out of groundsheets and shell boxes, a little too small for them as their feet were sticking out at the end, and their boots froze overnight, but at least it was dry and they felt sorry for the horses and mules, out all night without any shelter.

“The horses here got into a pitiable state being tied up in the open. Pools soon formed where they were stood and it being chalk soil when they laid down and daubed their backs and legs, in the mornings, if it had dried up a little with a wind they would be white horses. Grooming, it had to be done here on active service, so our jack-knives came into use, it being like cement on their backs. So we scraped them, brushing and combing was out of the question, poor horses. I have seen blood ooze out sometimes when scraped, perhaps hairs would come with the mud.”

His very first task was to take a load of 18 pound shells to Martinpuich, and this was his first experience of being under bombardment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOther places he took shells to are part of the mythology of the Somme: Mametz Wood, Delville, Trones Wood and High Wood, and all the former villages were simply ruins, though there were one or two bizarre survivals: “Fricourt-La-Boisselle and other villages: what had been once were all in ruins or nearly levelled down within a mile or so from here. I think at Fricourt it was where a crucifix of Jesus Christ was intact among all the ruins. It looked rather extraordinary.”

Graves were part of the scenery, eventually too common to be remarked upon. “Close to here there was a grave of a British corporal of a Lancashire regiment, his hat and stripes hung on to a cross, with his teeth and jaw-bones and his hand and part of his wrist on the grave. A little way from here in a shallow shell-hole was a dead German, a big chap laid flat on his belly with arms out-stretched. He had been there a bit - such is war.”

One night all the men were suddenly ordered on parade, and ordered to help to dig out four 4.5 howitzers.

“I shall never forget that night, the Germans and our guns going at it. The Major was there, stood on a bank of higher ground, shouting and cursing at the drivers, drag ropes were fastened to a ring on the nave of the wheel and the gunners had to get into the mud on each side of the gun and pull, the drivers on horseback whipping and striking at the horses. Some of the gunners was standing looking on while the drag ropes were being fastened, and what a curse came from the Major, him stood on dry ground, the gunners having to stand knee-deep pulling away till at last we got it out.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There was eight horses and four drivers, one man to two horses, the horses being up to their bellies in mud.”

This was actually Fred’s last action in France: as a consequence of this evening’s work he developed a high fever, was moved to Rouen on a hospital train and spent a month there in the Royal Canadian Hospital before being invalided home. However, his war was not over, and the next phase was even more bloody and harrowing.

• Next week, catch up on Alfred’s service in India.