The Great Escape: McKenna's legacy and possibly his greatest coup

Most poignantly, among the 50 victims were two fellow officers whom McKenna had known personally, Flight Lieutenant Edgar Humphreys and Flying Officer Robert Stewart. Humphreys, a pilot, born in Exmouth had, prior to the war, been stationed at RAF Squires Gate where McKenna had acted as Liaison Officer.

Long-term internees, both Humphreys and Stewart having seemingly successfully escaped from Stalag Luft III were last seen alive on March 31. Sadly their cremated remains were among the total of 46 urns and four boxes subsequently returned to the camp.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIntensive interrogations very quickly established the murders, the vast majority being committed on Good Friday, 1944, followed a similar pattern. A captured Prisoner of War would be driven back towards the camp by Gestapo officers, the car would stop, and the prisoner, having been released from his handcuffs, was invited to stretch his legs at the side of the road. As they did so, they were cold bloodedly shot in the back of the head. The bodies were quickly cremated, as the Gestapo then attempted to fabricate evidence purporting to show that all the prisoners had been shot while in the process of trying to escape.

Having established a list of wanted suspects, the team then embarked on the much more difficult and dangerous task of sweeping the many internment camps in the hunt for the murderers. Here, possibly McKenna’s greatest coup was to track down the murderer of the veteran airman, Squadron Leader Roger Bushell, known in the camp as Big X, the 32-year-old South African born, Cambridge educated barrister and international skier, who had been the principal organiser of the escape.

The suspect, identified as Emil Schulz, a former Gestapo official, McKenna found, arrested and extradited all in the course of a single day in 1946.

Following the interrogation over the phone of a fellow Gestapo officer held at SIB Headquarters in Princes Gate, London, McKenna had obtained a somewhat bland description of a block of flats in which Schulz had lived. After an initial search that proved fruitless, a stroke of luck sent him to the nearby village of Frankenholz.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHere he found Schulz’s wife, seemingly living alone and denying all knowledge of her husband. Unconvinced, he undertook a minute search of the building and discovered a most intimate love letter recently written on paper that emanated from a nearby French prison camp.

Subsequently finding Schulz masquerading under the name of Ernst Schmidt, McKenna successfully negotiated his immediate extradition.

However transporting his prisoner back to SIB Headquarters in London, proved an even more daunting task. Their initial Dakota aircraft could not get off the ground and a replacement Anson had to make a number of emergency landings, limping only as far as Manston Aerodrome in Kent.

McKenna then had to transfer to a crowded Margate to London holiday excursion train, standing in a corridor handcuffed to his prisoner. Aware he would not see his wife again, Schulz asked McKenna if he could write a note to his wife. McKenna nodded, and agreed to deliver it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen he returned back to Germany, as promised, McKenna duly travelled to Frankenholz to see Frau Schulz. After warning her she was unlikely to see her husband ever again he then handed over the letter. Allowing her time to read its contents, as requested, she then had to hand it back to McKenna. They then shook hands, said their goodbyes and McKenna drove away.

Schulz subsequently stood trial for war crimes, was found guilty and executed on February 27, 1948. In a most moving postscript, during a 2009 Channel Four television documentary entitled The Great Escape: The Reckoning, Schulz’s daughter, Ingeborg, read from the final letter her father had sent them as he awaited his execution.

Of the many other wanted men on his list, one, Erich Zacharias, he had to arrest twice. Having first brought him out of the Russian zone, at considerable personal risk, the suspect was “loaned” to the Americans who, much to McKenna’s disgust, let him go.

He was finally captured on April 1, 1946, as he attempted to get back into the Russian zone. Transferred to England to the supposedly escape-proof compound at Kempton Park Race Course, for a time Zacharias somehow even managed to disappear from there. Eventually recaptured, he too was subsequently executed for war crimes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs he had done with Emile Schulz, totally against regulations, McKenna once again agreed to hand deliver a final letter to his family.

Surviving several attempts on his life, altogether McKenna arrested some 26 former Gestapo officers, the largest single total out of the 69 men brought to justice. A few committed suicide before being tried, but a large number were convicted of murder and subsequently imprisoned or executed.

When, in September 1948, the Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin announced the British Government would no longer prosecute any further war crimes, the investigation gradually began to be wound down. That year, together with his commanding officer, Wing Commander Wilfred Bowes, McKenna was awarded the OBE.

Remaining with Special Investigation Branch, McKenna then moved on to serve in Cyprus during the EOKA troubles, once again being mentioned in dispatches. Spurning promotion to Wing Commander, he then returned back to the Blackpool Borough Police Force to complete his pensionable service.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThereafter, he joined the Ministry of Defence, where he specialised in vetting potential service personnel.

In 1971, aged 65, he retired for a second time, only to find his experience and expertise much in demand, subsequently working as a security consultant for a number of leading north west commercial companies.

A devoted family man, having married Eunice Bamber in 1930, McKenna himself had been touched by tragedy when, in 1943, elder son, Terry, was killed in a cycling accident. On completing his shift at Montague Street, he would spend time at his son’s graveside before proceeding home to Huntley Avenue in nearby Layton.

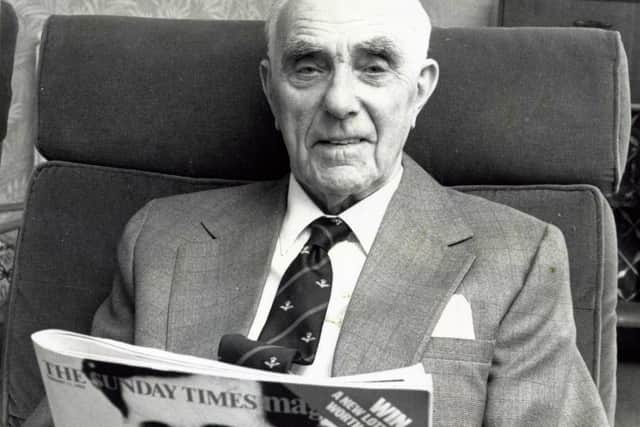

McKenna died, aged 87, on February 14, 1994. It was just a month before he had intended to be in the congregation at the 50th anniversary of “The Great Escape” when, at the Central Church of the Royal Air Force, St Clement Danes in London, a memorial service took place for the victims of the atrocity.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdToday, McKenna’s military manhunt remains a mere footnote in history.

Sadly, neither Anthony Eden, in what many consider to be his finest hour, nor Winston Churchill made mention of these events in their memoirs. McKenna himself also remained reticent about the episode – typically not wanting any fuss.

Seventy five years on, now is perhaps a pertinent time to remind everyone of his quite unique contribution to international justice.

In helping bring closure to this wartime atrocity and ensuring exemplary justice was done, Frank McKenna became something of a rare breed – one who helped a politician keep a promise.