When Mexican Joe came to Blackpool in 1890 his Wild West show was compared to that of Buffalo Bill

and live on Freeview channel 276

In the summer of 1890, the residents of Blackpool awoke to find Sioux and Apache camped in South Shore.

There were dozens of them, in tepees on waste land at the corner of Lytham Road and Tyldesley Road, where the Coliseum bus station would later stand.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Native Americans, together with cowboys and a few Mexicans, were part of a Wild West show its owner claimed to be ‘the Novelty of the Nineteenth Century’.

That man was Joseph Shelley, whom everyone knew as ‘Mexican Joe’.

He also claimed to be related to the poet Percy Shelley, and to have killed the king of the Apache in hand-to-hand combat.

None of that was true. In fact, Joe wasn’t even Mexican.

He had been born in Georgia, on a cotton plantation, and had fought for the South in the American Civil War. And after that, he had had all sorts of adventures in the American West.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMexican Joe’s show had come to England three years before, and for a while, it had been very popular.

There was a season in Liverpool, performed in honour of Queen Victoria’s jubilee. There were visits to towns across Britain, and to Paris and Naples as well.

But there were also unfavourable comparisons with Buffalo Bill.

His own Wild West show was the first to arrive in Britain, and it had been performed not just in honour of Queen Victoria, but in her presence.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd though Joe claimed his show was more true-to-life, he couldn’t deny that he had far fewer Native Americans than his illustrious competitor had.

The Blackpool show did at least have an illustrious opening, performed by the Mayor, Alderman John Bickerstaffe. And for the next couple months, for only sixpence-a-go, it could be seen twice-a-day, every day.

On Sundays, meanwhile, Joe would welcome anyone with another threepence to spend, and take them on a tour of the camp.

He would show them the canvas tent in which the show was performed. It was 150 feet wide and twice that long, and Joe would say that it was the biggest in the world.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe would show them the Native Americans, who had names such as Running Wolf and High Bear, and who lived in three large tepees.

There were cowboys in the camp as well – Montana Frank, Yellowstone Vic and the like – and the tents they lived in were clustered around a fourth tepee.

That, Joe would say, was where the most troublesome were kept – the ones who were ‘spoiling for a fight’. His own tent was next door, and he kept a close watch on what was going on.

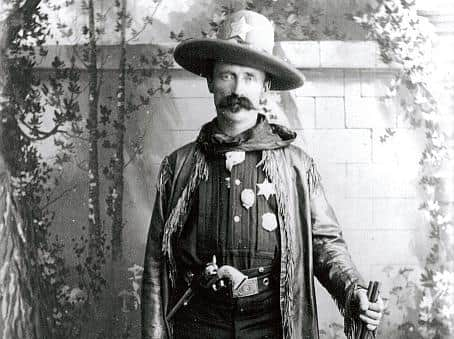

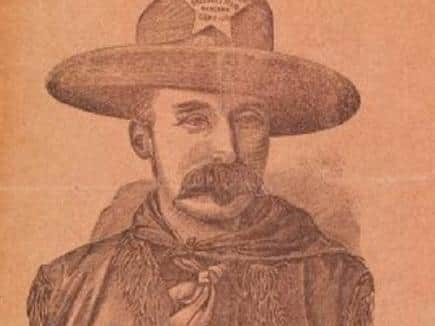

The show would begin at 2.30pm or 7.30pm, with Mexican Joe leading a big parade into the tent, wearing a black sombrero with a silver star on the front.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Sioux and Apache would follow him, one or two Pawnee as well, all of them resplendent in face-paint and feathered head-dresses.

Then, Joe would speak.

His face was lined and weather-beaten, even though he himself wasn’t yet fifty.

He had a walrus moustache and sad eyes. There were people who said that he was bald under the sombrero, but the story he told was undeniably sad.

He had been proud to serve as a captain in the Texas Rangers, he would say, and to serve in the US and Mexican armies as well.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe had been a cattle-rancher in Texas and Mexico, and a prisoner of the Apache for 15 months. And his wife and children had been brutally killed.

There would follow two hours of equestrian events, foot-races, lasso throwing, and bucking broncos.

Old Western skirmishes would be re-enacted, and a horse-thief lynched.

And the show would culminate in a loud and frenzied attack on a stage-coach, during which someone in the audience would invariably be overcome.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn the first night, that person might have been the man from the Blackpool Gazette & Herald. ‘The entertainment is the most exciting we have ever seen,’ he said the following day.

Excitement of one kind or another followed Mexican Joe around.

He lost much of the show in a fire in Manchester, although a whip-round quickly got him back on his feet. Then, a fortnight after he arrived in Blackpool, the show tent blew down in fierce gales.

He performed in the open air for a while after that.

There was also, however, excitement of a happier kind.

A few weeks later, after the tent had been put up again, it played host to the wedding of a Sioux squaw and an Apache brave.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe ceremony was a private one, held in the dead of night, with Joe the only witness who wasn’t an Indian.

Strange dances were danced, and strange foods eaten, and just before dawn, the peace of Lytham Road was shattered by the monotonous beating of drums.

Romance could be found wherever the tent was pitched.

In Liverpool, Montana Frank married a young woman who worked on one of the stalls. Eveline Johnson, meanwhile, had followed Yellowstone Vic to Sheffield from there, only to discover when she married him that he was really Arthur Cooper.

And Joe received a letter from another Liverpool girl, which read, ‘As I am in want of a husband, would you mind asking your cowboys, and the ones you know in America, if they want a wife?’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn Blackpool, something else happened that happened elsewhere as well.

The show had been running for barely three weeks when Running Wolf found himself up before magistrates in the town.

He had been found stumbling along Foxhall Road in a drunken state in the early hours of the morning, and he was fined two-and-six.

This was nothing new. Running Wolf was always getting himself into trouble, and for that reason, he was one of the natives forced to live in the tepee surrounded by cowboys.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was convicted of assaulting customers in Glasgow, Middlesbrough, Dublin. Often, indeed, he was apprehended while apparently in the act of scalping them.

In Leeds, when Running Wolf was had up for assault, Mexican Joe was had up as well, accused of resisting the constable who was trying to arrest the Indian.

Mexican Joe was always getting into scrapes himself.

In Blackpool, he was had up for allowing two horses to escape from the camp. It was because of the recent gales, he said, and the fact that his fences had been blown down.

But if the magistrates were sympathetic to him, some of the charges he faced were more serious.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe had let his dogs run wild, it was said, made his broncos buck by putting spikes under their saddles, and employed children who were much too young.

Invariably, he would appear in court not just in the sombrero, but in leather breeches as well, with a blue velvet tunic covered in gold brocade, an overcoat with a fur collar, and a chest-full of medals.

And he would look at the bench with his sad eyes, apologise for his nervousness, and explain that he had never been in court before.

A case heard in the summer of 1894 is perhaps most revealing. This one, too, featured Running Wolf, who was again alleged to have assaulted someone at a show. The victim this time wasn’t a customer, though, but the man employed to look after the Native Americans. And when that man stood up in court, he too seemed to have an injury to his scalp.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe defendant was one several who had turned on him, the man said, and who had complained – loudly and violently – that Joe was withholding their wages and keeping them short of food. The show was, frankly, on its last legs.

Joe found himself being sued by all kinds of people – people who put up his posters, or who had been kicked by his horses, or who supplied the carrots the horses ate. Performances were being cancelled. And if Joe’s name appeared on a bill, he was now more likely to be giving a lecture from an armchair than firing a revolver above his head.

The following summer, when he came back to Blackpool, it wasn’t to a big tent amid a village of tepees, but to a little booth on the sands that had to be dragged up onto the Promenade every time the tide came in.

There, Mexican Joe would greet his visitors in twos and threes rather than thousands, and start to recite his unbelievable story over again.

He had been proud to serve as a captain in the Texas Rangers, and to serve in the US and Mexican armies as well.