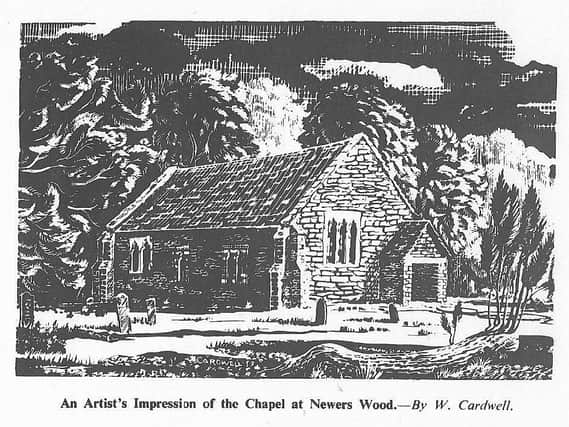

Retro: Mystery of long lost chapel by Pilling woods

In a remote corner of farmland by Newer’s Wood near the Wyre village of Pilling, there stands an elliptical piece of ground approximately 100 by 60 yards, and fronted by a moat some 18ft wide.

The site is fairly inaccessible these days but was once served by a road running from the junction of Lancaster Road and Horse Park Lane, as the mound is what remains of the medieval chapel of St John the Baptist.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe actual date of the chapel’s installation is lost in the midst of time, though traditionally believed to be built around 1209 by the monks of the nearby Cockersand Abbey and named after their favoured saint.

A detail in the Charter of Theobald Walter with Canons of Cockersand Abbey does suggests it may have already been in existence in 1194, though this could have been an earlier build as archaeological evidence was later to reveal.

The monks had installed a grange at Pilling Hall shortly after the foundation of the abbey and the chapel was very likely attached to it, though not physically as its site is about a quarter of a mile south of the Hall.

The wooded seclusion of the area and its existing designation as a place of worship would make it the ideal place for congregational activity, and this separation was later enshrined in a privilege bestowed to the Canons of Cockersand by Pope Honorius in 1217 granting their granges equal status to churches in terms of quiet seclusion.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1493 the Bishop of Lichfield granted licence to a former nun of the Priory of the Blessed Mary at Norton to take up residence in a solitary cell at or near the Pilling chapel. She was named Agnes Bothe but also known as Schepard.

She was still there in 1501, as confirmed by an entry in the Rental of Cockersand which reads “Md yat Annes Schepte hasse payn to James ye Abbott of Cockersand for her lyving-iis iid to me and vis viid to ye Convent.”

After the dissolution of Cockersand Abbey by Henry VIII in 1539 the sum of £2 a year was allowed for the retention of a curate at the chapel, which even in those days this was a small amount and seemingly not enough. In 1621 some 60 of the parishioners petitioned the king complaining that despite paying their tithes the chapel was neglected and no curate provided.

The petition resulted in the renewal of the annual £2 granted from the duchy revenues, a further £10 a year provided by the lay rector Sir Robert Bindloss from the tithes, £6 13s 4d from the farmer of the demesne and £8 raised by the locals. This provided the chapel with a new lease of life, though as things turned out for just under another century.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy 1716 the population of Pilling had increased to about 140 families and clearly the small chapel was no longer able to accommodate this number a parishioners.

The incumbent Rev John Anyon headed a petition to the Bishop of Chester praying that a larger replacement church might be built, and sited in the centre of the village for convenience of access.

Located a mile west, the new church had its keystone laid in 1717 and was consecrated in 1721. The old chapel and its grave yard were abandoned, possibly dismantled or left to ruin once anything useful was salvaged from it.

The replacement building went on to serve the community until 1887 when further increases in the population necessitated an even larger Gothic structure to be built next door, and this remains the designated church of St John the Baptist to this day.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFortunately its Georgian predecessor was kept preserved and still stands for the admiration of visitors, thus spared the fate of the original chapel. However, remnants of the medieval church are still to be found. A headstone from the original graveyard was later recovered and read: RICHARD SON OF CHRISTOPHER CLARK OF THIS TOWN WAS BURIED HERE FEB YE JXTH 1720. Given the date of internment, he would have been one of the last, if not the last, to have been buried there.

Other stones from the structure were reused as part of other builds around the area, in particular a piece of lancet window at the nearby Pilling Hall farm.

The font in the nearby St Mark Mission Church at Eagland Hill, built in 1869, is said to have come from the chapel and appears Saxon in origin.

An excavation of the Newers Wood site by the Pilling Historical Society in 1953 uncovered some remaining foundations including two altar bases, and from these the confirmation that the building was just 27ft long and 18ft long.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA rectangular altar stone was found a short distance from the site with an incised cross on each of its corners, and a depression in its centre which would have held a brass plate or relics from the bodies of saints.

Pieces of pottery and clay pipes were also unearthed, along with fragments of stained glass and a circular glass bead. The latter was identified by the British Museum as being fifth to seventh century and used in Saxon worship.

Perhaps the most important revelation uncovered by the excavations is the indication that the nave had a rounded end, which confirms its origin way before the assumed 1209 as the earlier Christian churches followed the Roman basilica design.

Being located within the circumference of a moat also suggests it had been a site of Pagan worship before the installation of a Christian oratory, which again conforms to the pattern of locations chosen for those early churches.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIndeed it is possible that the chapel began life as a keeill, referring to a small building which combined both Christian and Pagan beliefs and overseen by a druid like wise man. Keeills tended to be constructed with wood and loose stones, and thus later rebuilt as Christianity took a firmer hold and parishes evolved.

It is likely the chapel was erected by the monks of Cockersand was placed on existing foundations. This begs the intriguing question as to whether further secrets of an ancient past lie even deeper beneath the mound and waiting to be unearthed. If so maybe they will provide more clues as to the origins of this enigmatic lost church.