How the Fylde Coast celebrated the tradition of Halloween with its own Teanlay Night

and live on Freeview channel 276

Think you know Halloween?

Isn’t it just a kitschy American holiday invented to sell sweets to giddy children?

You may be surprised to hear that Halloween has been observed in the British Isles for thousands of years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOur American cousins simply took these old practices with them when they left for the New World and have carried on traditions we have almost forgotten.

The Victorian’s were not fans of what they saw as primitive ideals and opted to wash away the customs and traditions of rural Britain.

They attempted to homogenize the culture and eradicate the stranger, more disturbing pagan practices of the past.

However, the dark customs of our ancestors lingered on, spoken about in hushed voices by country folk under the harvest moon.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHalloween or All Hallows Eve has had many names, including Hallowmas, Allhallowtide and the Celtic Samhain. On the Fylde Coast, our traditional name for Hallowe’en was Teanlay Night.

Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable from 1894 describes it as “the vigil of All Souls, or last evening of October, when bonfires were lighted and revels held for succouring souls in purgatory”.

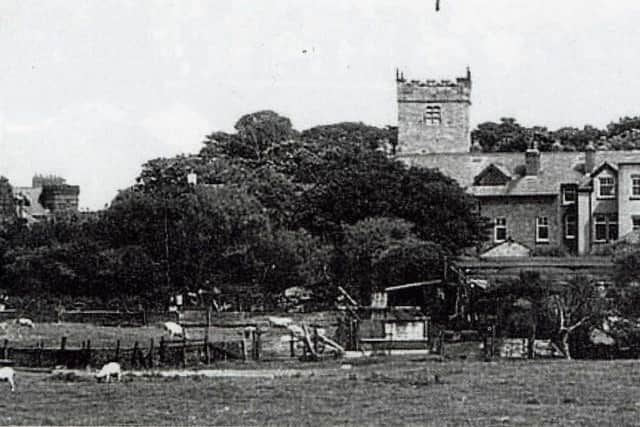

At Poulton-le-Fylde there was an old meadow known as the Purgatory Field.

On Teanlay Night people from across the Fylde plain would gather in this field around a great bonfire or bone-fire, where the clean bones of animals and white stones would be roasted in offering instead of wood.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe light of the flames was believed to guide the souls of loved ones who had departed in the last year out of purgatory and beyond the veil to the next life.

Also, the fire would keep those in its presence safe from the mischievous and malevolent spirits that walked abroad that night and protect the crops from weeds and pests in the coming year.

Victorian historian William Thornber wrote that on the “Hardhorn oblong cairn, ceremonies were observed for the purpose of securing health to the herds of the farmers in the township to free the wheat-land from tares and weed to bring good luck to the votaries, and to enquire into the secrets of futurity.

The ceremony was thus: first, large fires were lighted, two or three families joining at a circular cairn, the ashes of which were carefully collected. Then the white stones, which at first had circled the fire, were thrown into the ashes, and being left all night, were sought for with anxious care at sunrise when the person who could not distinguish his own particular boulder was considered - some misfortune would happen to him during the course of the ensuing year.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs a finale, the stones recognised were thrown, as an offering, on the oblong cairn to the god or saint who presided over it and the well, and thus such collections were made in a succession of years as to astonish the curious. The water of the wells also had a sovereign virtue for healing diseases of men and cattle. Fairy well is even yet visited for such a purpose. To succeed in obtaining a cure, however, the patient, escorted by his friends, was made to pass through the cairn, then he was sprinkled or dipped in the well, and lastly, he made an offering of a shell, a pin, a rusty nail, or rag, but principally three white stones burnt in the Teanlay fire.

It is surprising in what numbers pieces of iron may be picked up. I have found since the meadows were ploughed, nails, an old shaped knife, leathern thongs, &c. The site of the large circular cairn is not now easily to be distinguished, since Mr. Fisher, the proprietor of the field, has carted away upwards of twenty loads of the refuse that composed it, but the soil around is burnt red and black. This farce was carried on in its pristine glory long after the Reformation; for rational Christianity, which had been almost lost previously, progressed but slowly in the district of the Fylde.”

The memory of Teanlay Night persisted into the 20th century and it even gave its name to the modern day Teanlowe Shopping Centre, which is built adjacent to the original Teanlay field.

All modern Hallowe’en traditions can be traced back to the rites performed by our ancestors.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPumpkins originate from the carved turnip lanterns that were lit to guide the dead. These lanterns mimicked that carried by Jack-O’-Lantern, the doomed Irish spirit cursed by the Devil to walk the night for eternity, led only by the flickering flame of his lantern.

Hallowe’en costumes come from the disguises or cloaks folk would wear to go ‘guising’, covering themselves up so the goblins and boggarts wouldn’t recognise them. Wearing a mask or painting your face meant you would go unnoticed by the spirits. Trick or Treating stems from the tradition of ‘souling’, where bands of children would go from door to door, singing songs for the reward of spiced soul cakes or harcakes, which were pauper cakes given in charity. Parkin was eaten at this time of year, just as we do now. It was made from treacle and oats, because oats were in surplus due to the annual grain harvest at the end of October. Magic was always connected to Hallowe’en. The rural folk of the Fylde performed rituals with apple cores or peel, to tell their fortunes or see the initials of their future lovers. Witches were feared on Hallowe’en. The people of Lancashire would light ‘witch candles’ and walk up into the fells to ‘late’ or ‘leet’ the witches, a word derived from the Saxon ‘leoht’ meaning light. This was thought to offer protection to the community from witches for the following year.

The people of this coast believed that it is important to remember our dead so that we may appreciate those that still live, something that strikes a chord in a post-pandemic world.